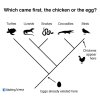

It’s that old riddle that’s sparked many arguments through the ages: was it the chicken or the egg that came first? It’s such a tricky question because you need a chicken to lay an egg, but chickens come from eggs, leaving us with an intractable circle of clucky, feathery life that apparently has no clear starting point.

Thankfully, there’s no need to keep brooding over this forever. This is a riddle we can unscramble with the tools of science—more specifically, the principles of evolutionary biology.

Let’s get cracking.

But let’s focus on the type of bird's egg we recognise today. These first came on the scene with the evolution of the first amniotes many millions of years ago. Prior to their arrival, most animals relied on water for reproduction, laying their eggs in ponds and other moist environments so that the eggs didn’t dry out.

At some point, a different kind of egg began to evolve, which had three extra membranes inside: the chorion, amnion and allantois. Each membrane has a slightly different function but the addition of all these extra layers provided a conveniently enclosed, all-in-one life support system: an embryo can take in stored nutrients, store excess waste products and respire (breathe) without the need of an external aquatic environment. The extra fluids encased in the amnion, plus the tough outer shell, provide extra protection too.

Amniotic eggs were a big deal. They opened up a whole new world of opportunities for land-based egg-laying locations, and the extra membranes paved the way for bigger (and mostly better) eggs.

We’re still not sure of exactly when this happened, largely because eggy membranes don’t make very good fossils, leaving scientists with no clear record of when, or how, amniotic eggs developed. Our best guess is that the last common ancestor of both tetrapods (four-limbed animals with a backbone) and the amniotes (four-limbed animals with a backbone that lay eggs with all those extra layers) lived around 370-340 million years ago, though some sources put the first amniote species as living closer to 312 million years ago. Today’s mammals, reptiles and birds are all descendants of the first amniotes.

(This leaves us with another eggsellent question: which came first, the amniote or the amniotic egg? But let’s just stick with chickens for now.)

So who were the likely parents of this first One True Chicken? The red junglefowl (Gallus gallus) is native to a range of south-eastern Asian countries including India, southern China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia. It’s thought that the red junglefowl was domesticated by humans in Asia and went on to be spread around the world as the less-aggressive and prolific egg-layers that we know and love today (Gallus gallus domesticus).

Archaeological evidence suggests that the red junglefowl was first domesticated some 10,000 years ago, although DNA analysis and mathematical simulations suggest that the domestic chicken actually diverged from junglefowl much earlier (an estimated 58,000 years ago). There’s also evidence to suggest that the domestic chicken’s origins may be slightly more complicated: the genes for the yellow colour seen on the legs of many chooks could have come from the grey junglefowl (Gallus sonneratii), not the red, pointing to some hybridisation between species somewhere along the way.

Back to our original question: with amniotic eggs showing up roughly 340 million or so years ago, and the first chickens evolving at around 58 thousand years ago at the earliest, it’s a safe bet to say the egg came first.

Thankfully, there’s no need to keep brooding over this forever. This is a riddle we can unscramble with the tools of science—more specifically, the principles of evolutionary biology.

Let’s get cracking.

The first eggs

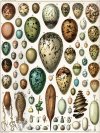

Eggs are found throughout the animal kingdom. Technically speaking, an egg is simply the membrane-bound vessel inside which an embryo can grow and develop until it can survive on its own.

But let’s focus on the type of bird's egg we recognise today. These first came on the scene with the evolution of the first amniotes many millions of years ago. Prior to their arrival, most animals relied on water for reproduction, laying their eggs in ponds and other moist environments so that the eggs didn’t dry out.

At some point, a different kind of egg began to evolve, which had three extra membranes inside: the chorion, amnion and allantois. Each membrane has a slightly different function but the addition of all these extra layers provided a conveniently enclosed, all-in-one life support system: an embryo can take in stored nutrients, store excess waste products and respire (breathe) without the need of an external aquatic environment. The extra fluids encased in the amnion, plus the tough outer shell, provide extra protection too.

Amniotic eggs were a big deal. They opened up a whole new world of opportunities for land-based egg-laying locations, and the extra membranes paved the way for bigger (and mostly better) eggs.

We’re still not sure of exactly when this happened, largely because eggy membranes don’t make very good fossils, leaving scientists with no clear record of when, or how, amniotic eggs developed. Our best guess is that the last common ancestor of both tetrapods (four-limbed animals with a backbone) and the amniotes (four-limbed animals with a backbone that lay eggs with all those extra layers) lived around 370-340 million years ago, though some sources put the first amniote species as living closer to 312 million years ago. Today’s mammals, reptiles and birds are all descendants of the first amniotes.

(This leaves us with another eggsellent question: which came first, the amniote or the amniotic egg? But let’s just stick with chickens for now.)

The first chickens

The very first chicken in existence would have been the result of a genetic mutation (or mutations) taking place in a zygote produced by two almost-chickens (or proto-chickens). This means two proto-chickens mated, combining their DNA together to form the very first cell of the very first chicken. Somewhere along the line, genetic mutations occurred in that very first cell, and those mutations copied themselves into every other body cell as the chicken embryo grew. The result? The first true chicken.

So who were the likely parents of this first One True Chicken? The red junglefowl (Gallus gallus) is native to a range of south-eastern Asian countries including India, southern China, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia. It’s thought that the red junglefowl was domesticated by humans in Asia and went on to be spread around the world as the less-aggressive and prolific egg-layers that we know and love today (Gallus gallus domesticus).

Archaeological evidence suggests that the red junglefowl was first domesticated some 10,000 years ago, although DNA analysis and mathematical simulations suggest that the domestic chicken actually diverged from junglefowl much earlier (an estimated 58,000 years ago). There’s also evidence to suggest that the domestic chicken’s origins may be slightly more complicated: the genes for the yellow colour seen on the legs of many chooks could have come from the grey junglefowl (Gallus sonneratii), not the red, pointing to some hybridisation between species somewhere along the way.

Back to our original question: with amniotic eggs showing up roughly 340 million or so years ago, and the first chickens evolving at around 58 thousand years ago at the earliest, it’s a safe bet to say the egg came first.